Whether you create your own code-signing certificate, or use a certificate from a certificate authority, it’s easy to give your Windows binaries the seal of approval.

If you compile programs on Microsoft Windows to a binary, you may have noticed that the resulting binaries don’t always run on other machines—at least, not without Windows objecting. As a security measure, Windows can be configured to run only binaries that have been digitally signed by a trusted authority.

Signing binaries on Windows requires a digital certificate. If you create a binary you want to distribute to the world at large, you’ll want to obtain a code-signing certificate from a certification authority. However, if you just need to sign code for your own internal testing—for instance, to ensure a signed binary behaves as expected—you can create your own self-signed test certificate.

Buying a code-signing certificate

Buying a certificate from a certificate authority (CA) is the simplest and most comprehensive option for code signing. The major trusted certificate providers, such as Verisign, Thawte, and Comodo, all sell certificates for code signing.

The downside is that commercial code signing certificates aren’t cheap. The simplest code-signing certificates start at around $129/year and can exceed $600/year. The per-year cost reflects the fact that a certificate expires, meaning it can be used to sign code only for a predefined span of time, typically one year. Although any code signed with the certificate remains valid forever, you can’t sign new code with a certificate once it expires.

Why so expensive? For one, there is a sliding scale of trust for certificates. A simple code-signing certificate provides only a small range of guarantees about the signed binary. The more expensive “extended validation” (EV) code signing certificates provide stronger guarantees against tampering. For instance, the certificate may be distributed on a FIPS-compliant hardware token to make it difficult to steal.

EV certificates also allow the signed binaries to be trusted by Microsoft Windows’ SmartScreen reputation service, so that downloads of signed binaries aren’t blocked by Microsoft Edge or Windows generally. If you plan to develop device drivers for Microsoft Windows, you must use an EV code signing certificate.

Generating a self-signed code-signing certificate

If you need a code-signing certificate only for the sake of your own local testing, you can generate your own “self-signed” certificate.

Self-signed certificates are exactly what they sound like. They’re signed by you alone, so aren’t part of the “chain of trust” that certificate authorities participate in. As a result, anything you sign with a self-signed certificate will not be trusted in the wild; it will only be trusted in the environment where you recognize the certificate. But if all you need is to sign code for your own testing, as a prelude to signing code with a CA-backed certificate, you can self-generate a cert and use it as a temporary measure.

Generating a self-signed certificate on modern Windows systems is a multi-step process, but Windows Server 2025 and Windows 11 PowerShell come with a built-in command, New-SelfSignedCertificate, that makes the process automatable.

Digitally signing code on Windows, step by step

Let’s walk through the steps. If you’re using a self-signed certificate to sign your Windows binary, you’ll step through the entire process outlined below. If you’re using a CA certificate, then you only need to follow steps 1 and 6.

Step 1: Make sure you have the Visual Studio prerequisites

Signing code with a certificate on Windows, regardless of how you obtain the certificate, requires a tool that is typically shipped with Microsoft Visual Studio, called SignTool.

If you don’t have Visual Studio installed, you don’t need to install the full, commercial version of it to get SignTool. You can install the free-to-use, command-line only components for Visual Studio and the Microsoft Visual C++ Build Tools using WinGet:

winget install -e --id Microsoft.VisualStudio.2022.BuildTools --force --override "--passive --wait --add Microsoft.VisualStudio.Workload.VCTools;includeRecommended"

Once you’ve set up Visual Studio, you’ll want to execute all the commands described here from the Developer prompt command-line environment. If you launch the Terminal app, you’ll get Developer PowerShell as one of its options. Right-click on that and select “Run as administrator” to launch an elevated session of PowerShell. Be sure to use that shell session for all of the commands shown here.

If you’re working with a pre-generated certificate from a certification authority, you can skip ahead to step 6. Otherwise, if you’re working with a self-signed certificate, read on.

Step 2: Generate a fake root authority for your machine

The first step is to create a self-signed “root authority” certificate. This will simulate one of the major certificate-issuing authorities, but only on our local machine.

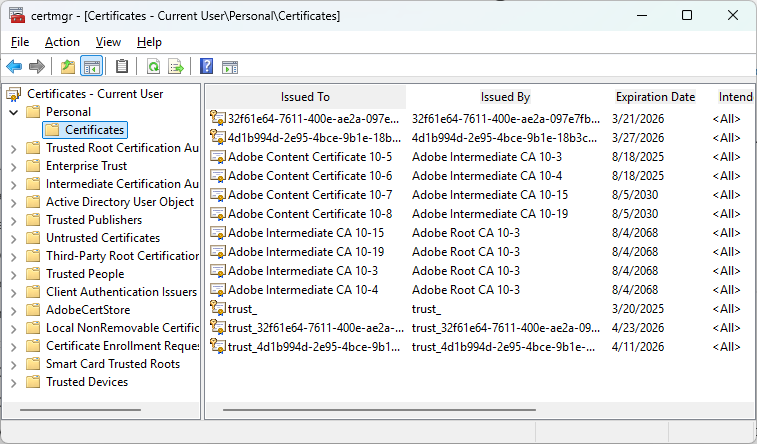

First, open the Certificate Manager in the Microsoft Management Console (MMC) for the current user. You can get there quickly by typing “user certificates” in the Start menu. This should bring up an icon labeled “Manage user certificates.” Click it and you’ll open the MMC with the certificates for the current user.

Click on Personal in the left-hand pane, then Certificates. This gives you a list of all the personal certificates present for the current user.

The certificate manager snap-in for Windows. Self-signed certificates will be generated here by default with the steps listed in this article.

IDG

Next, open the Developer PowerShell prompt (as mentioned above) and issue the following command.

$rootCert = New-SelfSignedCertificate -CertStoreLocation Cert:\CurrentUser\My -DnsName "FakeCA" -Type CodeSigning

Important: Do not close the PowerShell session you’re using! After you run the above command, a reference to the certificate will be stored in the shell variable $rootCert.

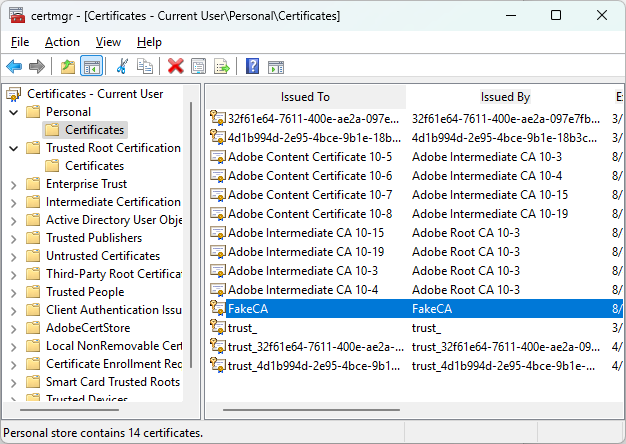

If you hit “Action | Refresh” in the certificate manager window, you should see a new certificate named FakeCA appear in the right-hand pane.

The newly generated fake certificate authority is now available in the user\’s certificate store. Anything signed with this certificate is only valid if we trust it on the same machine.

IDG

That’s your newly generated self-signed certificate.

Step 3: Export the root authority certificate

Next, we need to export the certificate to a .pfx file so we can re-use it readily. To do this, we have to password-protect the certificate to protect it from tampering—yes, even if it’s a test certificate.

There are two ways to do this: through the MMC interface, or through the command line. The MMC interface is easier. You right-click on the new certificate, select “All Tasks | Export”, and follow the prompts to export including the private key. However, the PowerShell commands are more flexible, so we’ll detail them here.

We use the following PowerShell commands in the same session.

[String]$rootCertPath = Join-Path -Path 'cert:\CurrentUser\My\' -ChildPath "$($rootCert.Thumbprint)"

This gets the path to the certificate in the store, by way of the $rootCert variable we stored earlier. (This is why you want to issue all of these commands in the same shell session, so the references to the generated certificates can be re-used.)

Next, we will use that certificate to generate two files, named FakeCA.pfx and FakeCA.crt, in your current working directory. FakeCA.pfx is the private key associated with the certificate, without which we can’t use it, and which must be password-protected. FakeCA.crt is the certificate itself, written out to a file.

Export-PfxCertificate -Cert $rootCertPath -FilePath 'FakeCA.pfx' -Password ("password" | ConvertTo-SecureString -AsPlainText -Force)

Export-Certificate -Cert $rootCertPath -FilePath 'FakeCA.crt'

In the code above, substitute in your own password where it says "password". Be sure to retain the quotes.

Step 4: Create a new certificate signed by the fake root authority

This next step generates an actual certificate signed by the fake root authority we created for this machine. Again, use the same PowerShell session for these commands too.

$testCert = New-SelfSignedCertificate -CertStoreLocation Cert:\LocalMachine\My -DnsName "SignedByFakeCA" -KeyExportPolicy Exportable -KeyLength 2048 -KeyUsage DigitalSignature,KeyEncipherment -Signer $rootCert

As with the fake root authority, this certificate is kept in the machine’s local certificate store.

We also need to export the certificate and its private key to two files, as we did before. Be sure you use the same password for the private key that you defined above.

[String]$testCertPath = Join-Path -Path 'cert:\LocalMachine\My\' -ChildPath "$($testCert.Thumbprint)"

Export-PfxCertificate -Cert $testCertPath -FilePath testcert.pfx -Password ("password" | ConvertTo-SecureString -AsPlainText -Force)

Export-Certificate -Cert $testCertPath -FilePath testcert.crt

Once again, when you’re done, you should have two files, named testcert.pfx and testcert.crt, in your current working directory.

Step 5: Install the fake root authority certificate to the Trusted Root Authorities Store

The next step is to make the fake root authority we created into a fully trusted authority on this machine. When we do this, all certificates signed by that authority will be treated as trusted (again, only on this machine). Then we can sign any number of certificates with that authority and have them all automatically be trusted in the same environment.

However, this will only work on a machine where the fake root authority certificate has been set up to be trusted. That’s by design. Self-signed certificates should work only in environments where we designate them as trustworthy.

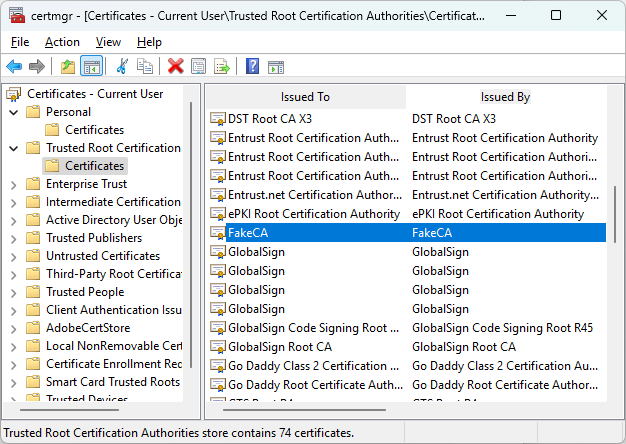

To trust the fake root authority, go back to the Certificate Manager snap-in. In the right-hand pane, expand “Trusted Root Certification Authorities | Certificates”, then right-click Certificates and select “All Tasks | Import”.

A wizard will prompt you to select a certificate file to import. Select your exported FakeCA.crt file and place the certificate in the Trusted Root Certification Authorities store. You’ll get a security warning and confirmation prompt asking you if you want to install the certificate. Select Yes.

When you’re done, you should see the FakeCA certificate show up in the store.

Adding the fake root authority certificate to the trusted root certification authorities store. Anything signed with this certificate is now trusted on this machine.

IDG

Step 6: Sign the code with SignTool

If you’ve created a fake root authority certificate, you’re now fully equipped to sign binaries. If you’ve acquired a code-signing certificate from certificate authority, you should have received with it instructions on how to set it up on the machine where you want to do the signing, and how to create a certificate file as we did above for our self-signed certificate.

In a new PowerShell session or the one you already opened, navigate to the directory where you have the binary you want to sign. You may want to make a backup copy of the binary before signing, just in case.

To sign the binary with your certificate, run SignTool and its sign command as follows.

signtool.exe sign /f Path\To\cert.pfx /p password /t http://timestamp.digicert.com /fd sha256 your_program.exe

Here’s what each of the above options does:

/fprovides the path to the .pfx file for your certificate. If you used a self-signed certificate, use the testcert.pfx file we exported before. Remember to enclose the path in quotes if it includes spaces./pprovides the certificate password we used earlier./tprovides a URL to a time service that can be used to timestamp the signing. This is important because it allows the signature to remain valid even after the original certificate expires./fdsets a hash algorithm for the signature, which is typically SHA256.your_program.exeis the binary to be signed.

Once you’ve run the SignTools sign command, you should see the following output.

Done Adding Additional Store

Successfully signed: your_program.exe

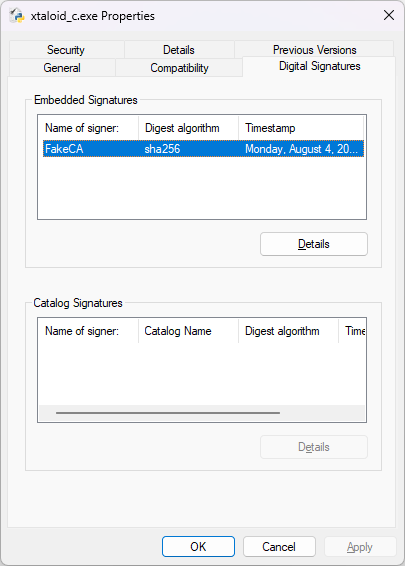

If you right-click on your program in Explorer and select “Properties | Digital Signatures”, you should see FakeCA listed under Embedded Signatures as shown below.

A signed binary will show its embedded signatures in the Digital Signatures pane of its file properties.

IDG

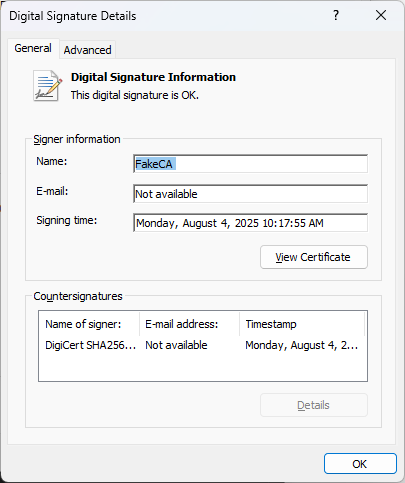

If you select the details for the root signature, you should see more information about the signing as shown below.

Details about the self-signed binary’s digital signature. “The digital signature is OK” indicates the signature is accepted as valid on that system.

IDG

Using self-signed certificates in other systems

Binaries signed with third-party code-signing certificates should be valid anywhere, since they’ve been signed with a trusted root authority certificate.

Self-signed code, though, will only be valid on the machines where you’ve installed the fake root authority certificate. If you need the signed binaries to be recognized as valid on multiple machines, you’ll need to import your FakeCA certificate into those machines and trust the certificate there, as described above. This is why we exported the certificates to files: to make it easier to pass them around and use them for signing on multiple machines.