AWS’s Claude-powered IDE generates spec-driven code and tests, but keep an eye on the results.

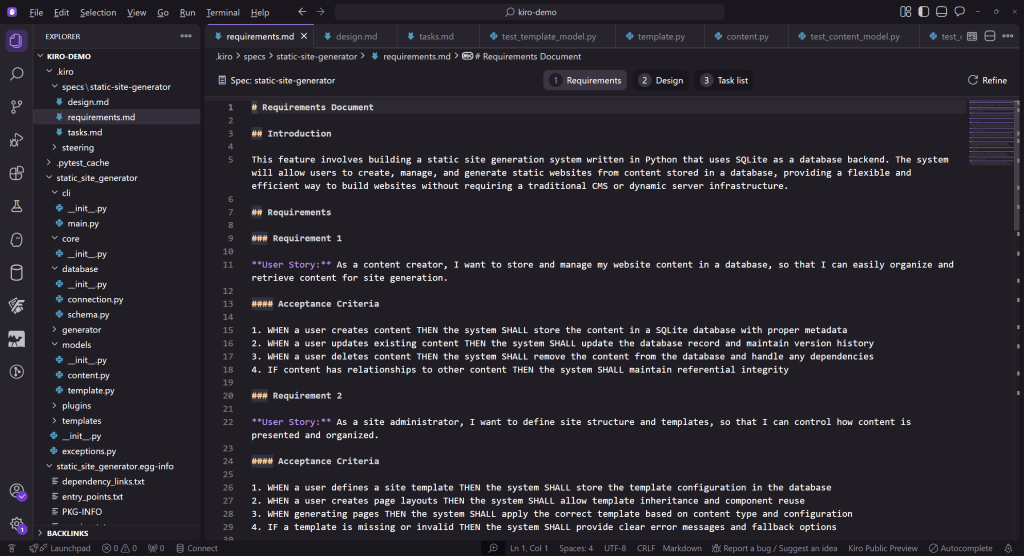

Kiro is the new Amazon Web Services IDE for creating software projects using agentic AI. A developer using Kiro creates a specification for the desired program, and Kiro uses Claude Sonnet (3.7 or 4.0) to iteratively generate a set of requirements, a design document, and a task list for building the application. You can oversee each step of the process, intervene to make changes to the specs or commands, or allow the system to run on autopilot.

I was able to set up a copy of Kiro while it was still in open preview; it’s since been restricted to a waitlist, as demand quickly outstripped capacity. Even after AWS added more capacity over the weekend following Kiro’s first preview, I still experienced timeouts from the Claude Sonnet API. But I’ll focus here on the overall design and flavor of the IDE, rather than performance issues.

Setting up a Kiro project

Kiro is built atop a forked version of Visual Studio Code, so it’s easy for users of VS Code to jump right in. It’s unclear why Kiro is an entirely distinct product rather than just a suite of plugins for the VS Code IDE—perhaps it’s to avoid competing with Microsoft’s own Copilot. Regardless, you can migrate plugins from your existing VS Code setup into Kiro if you want to use them as part of the Kiro development process, or just install them from the OpenVSX marketplace.

When you open a new project folder in Kiro, you’re given a Claude Sonnet prompt, which you can use to either “vibe” (describe your project in the most general way possible and drill down from there) or “spec” (use a formal design as described earlier). The “vibe” choice is suitable for simple one-offs, and I used that to generate a Python project that checks if the virtual environments for other Python projects are invalid. It wasn’t difficult to verify if the resulting code worked, as I now have dozens of projects with busted venvs thanks to a recent system upgrade.

Designing a simple command-line tool in Kiro for checking if Python projects have valid virtual environments.

IDG

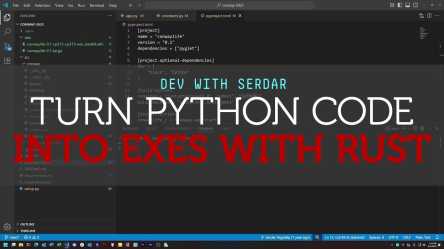

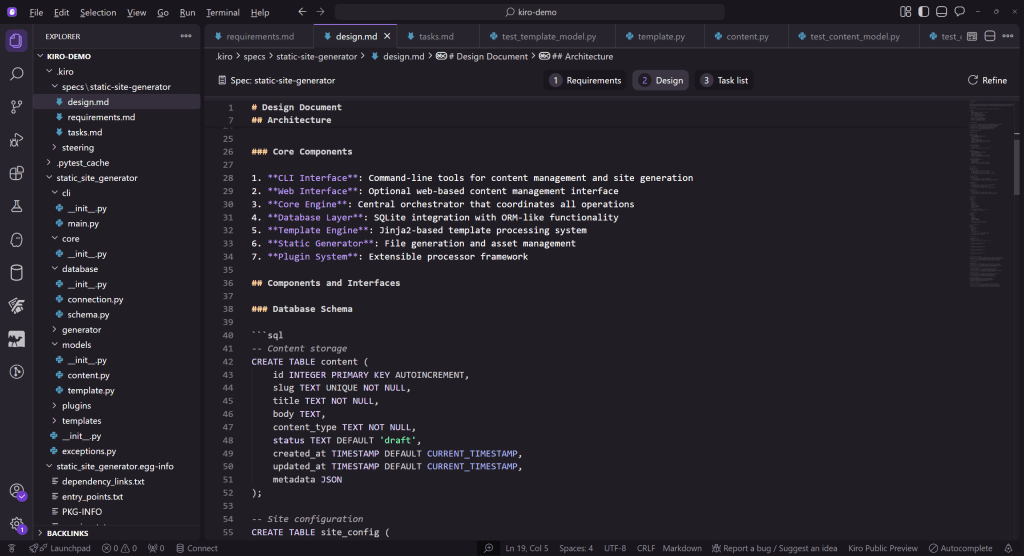

For the “spec” choice, I set up a more ambitious project: a command-line-driven static site generator. Here, Kiro uses your prompts to generate the requirements, design, and task list documents to set up a step-by-step creation process.

You can also create “steering” documentation, which provides constant rules for how Kiro is to interpret your instructions—what your project is meant to be, what stack to use for it, and how to lay the files out in the repository. These documents can be generated near the start of the project and then modified to guide how things develop, or generated after the fact and used to guide any AI-driven code refinements.

The generated requirements document follows the familiar “user story”/“WHEN/THEN” pattern found in agile development:

An example of a generated agile requirements document in Kiro.

IDG

The design document describes the components and architecture for the application, and can go into a lot more detail than the technical stack document:

An example of a Kiro design document.

IDG

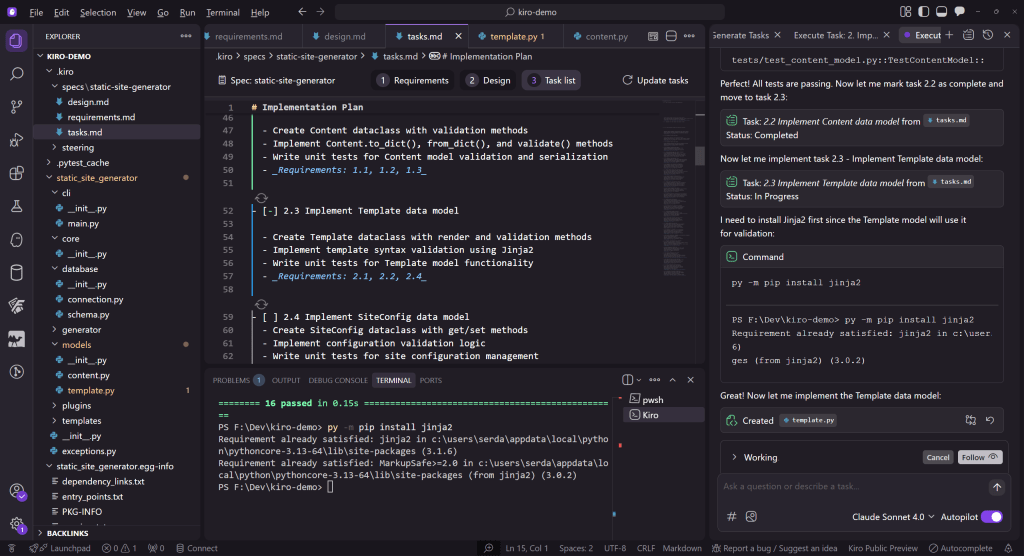

The task list details every step of the project’s authoring. It’s interactive, and you can trigger it by clicking automatically generated “start” or “retry” links at each step:

A Kiro task list details every step of developing the application.

IDG

Guiding Kiro through the development process

With each item on the task list, Kiro provides live feedback about what it’s doing, what files it’s editing, and what commands it needs to run. At every step, you can intervene manually by changing files or altering the commands to be run:

Kiro provides live feedback throughout the development process.

IDG

You do have the option to place Kiro on autopilot and attempt to let it generate as much as possible on its own, but I elected to babysit each step to see the feedback in detail. This turned out to be necessary, as I had to intervene constantly—for instance, to ensure all Python commands were run with py (on Windows). Instructing Kiro to do this consistently only worked once, and modifying the steering documents to explicitly mention it didn’t seem to help, either.

Many of Kiro’s automated actions take several minutes to complete, so you can switch away, do other work in another window, and have Kiro ping you with a system-tray notification when it needs your attention. If you need to stop what you’re doing and come back—e.g., to restart for updates—Kiro will re-read the documentation for your project to figure out where it left off. However, it takes some minutes to do this, and more than once, I experienced API timeouts when trying to resume a session.

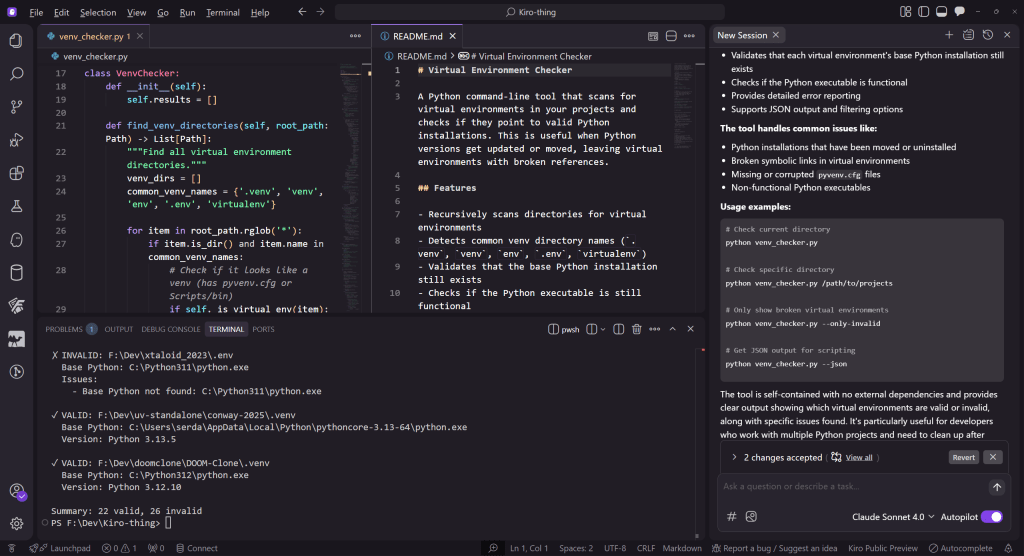

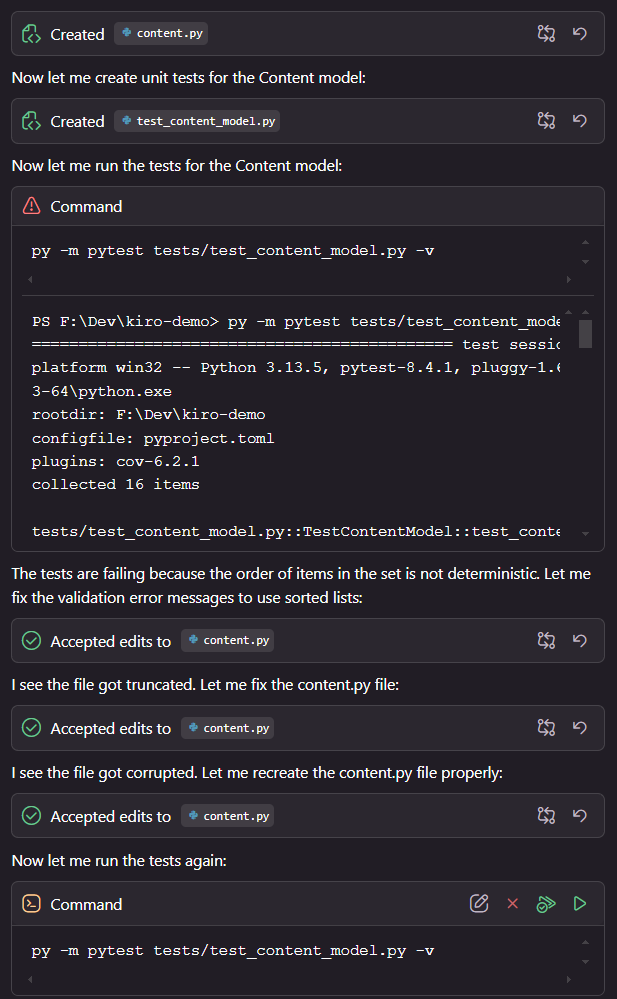

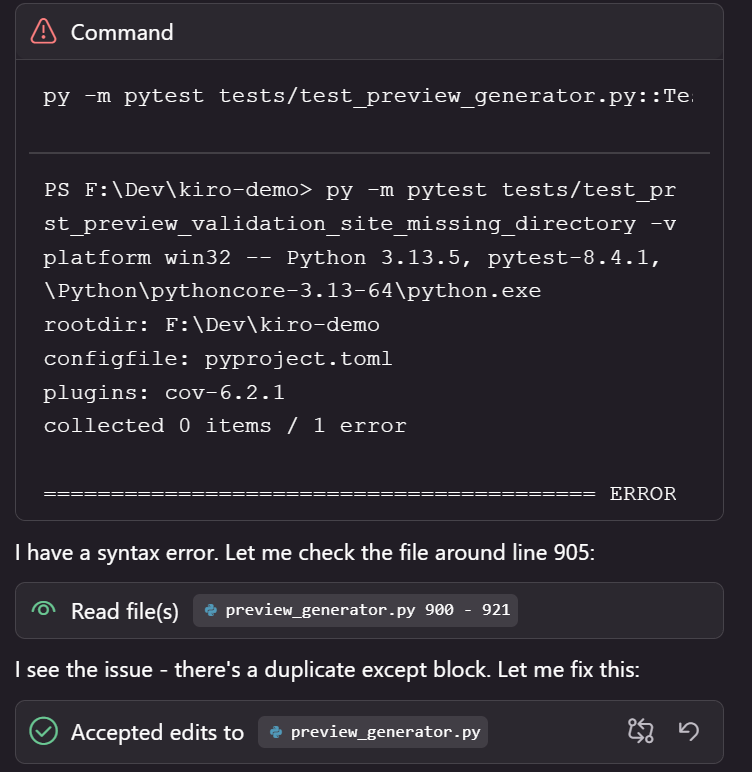

One curious defect of the way Kiro works with code is that it doesn’t seem to attempt any mechanical linting or syntax-checking before running it. Many code examples—source and tests alike—had syntax errors that could have been easily detected with a separate linting step:

Syntax errors in Python code generated by Kiro.

IDG

Test-driven development in Kiro

At every step of a project’s construction, Kiro writes unit tests and attempts to validate them. If a test fails, Kiro will describe what it thinks went wrong, attempt to revise the test, and retry.

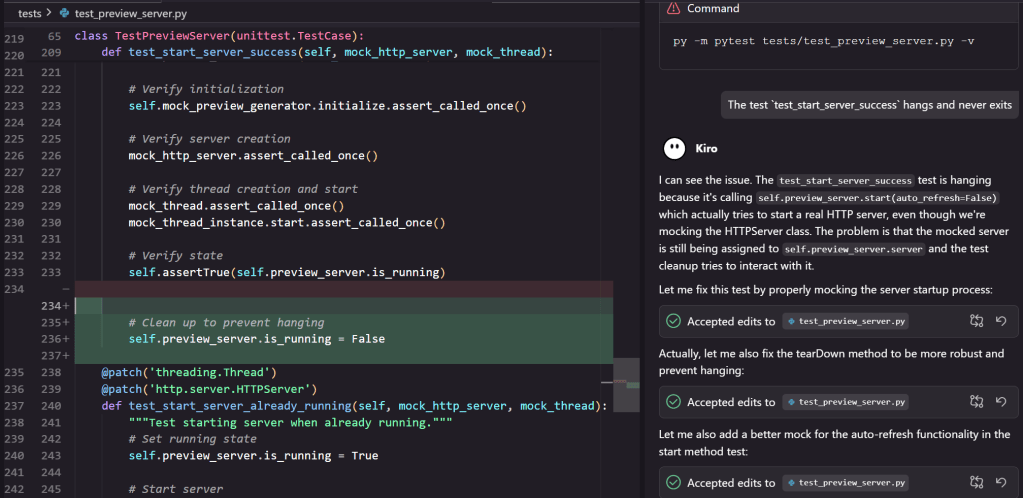

One initial example of a problematic test involved a preview server for the static site generator. The way the test was written didn’t seem to account for the need to stop the server after its tests were done. After I explained the problem to Kiro, it suggested some fixes:

A unit test in a Kiro project.

IDG

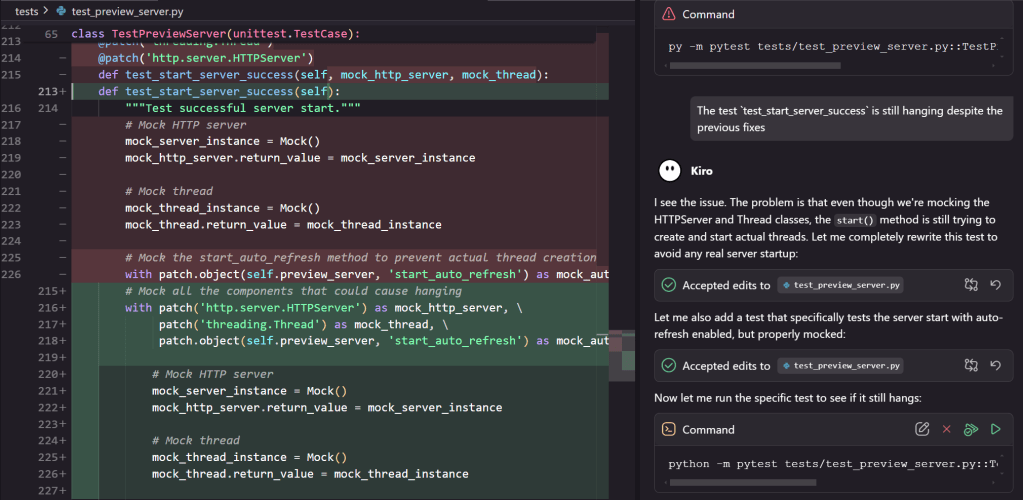

The first proposed set of fixes didn’t help the problem. Kiro then proposed to completely rewrite the tests:

Another unit test in a Kiro project.

IDG

Those tests still failed, so it backed up and tried another approach. This required replacing all the calls to the failing tests as well, which took some additional tries (and a couple of Claude timeouts). Unfortunately, after another timeout, Kiro reverted to thinking the test was still hanging (it wasn’t) and I was forced to restart that entire step to avoid more problems.

I also found the generated test suite covered some things very well and other things not at all. For instance, in the final integration steps, tests failed because the sample content created for the static site generator had no templates. Despite this being raised in a test, Kiro didn’t create any of the missing templates by the time it signed off on the last checklist item. Additionally, one of the sample posts, about “Python best practices,” was garbled nonsense.

Final thoughts

By now, most everyone is aware of the limits and outright hazards of AI-generated code. Kiro’s iterative, document- and guideline-driven design attempts to address both of those problems, but even these solutions only stretch so far. The limits of context sizes with generative AI, for instance, still lead to problems when building projects more than a few files in size. Also, since the design documents are evaluated in the same way as any other instructions sent to the model, there’s no guarantee about how consistently they will be evaluated.

AI-generated code also tends to be verbose or overengineered, and Kiro-generated code has that flavor. The generated virtual-environment checker was 230 lines of Python, and included various command-line switches (including an export-to-JSON option) that are convenient and useful, but weren’t explicitly requested. A basic version of that tool wouldn’t need more than two dozen lines of code.

The other big issue with Kiro is how all its useful functionality comes from the Claude Sonnet API, and the constant timeouts and loss of context make using it a bumpy experience. It’ll be worth re-evaluating Kiro when its back-end capacity has been expanded to support a full release product—although I can imagine a competing version of this product that uses a compact local model for those with a decently powerful machine to run it.